In 1970, Dieter Rams penned his Ten Design Principles. The state of design was, at the time, “an impenetrable confusion of forms, colours and noises”, and so he felt compelled to start exploring what makes a design truly Good. Was he just adding to the noise? From ‘No. 1: Good Design is Innovative’ all the way through to ‘No. 10: Good Design is as little design as possible’, Rams aimed to distil the essence of Good Design (you can see the full list explained on the Vitsœ website). These principles have been incredibly influential over the years – but they aren’t and can never be the final word on design. Humans have been chasing ‘Good Design’ for as long as they’ve been designing, and Rams’ iteration was as much shaped by the culture he inhabited as any other attempt at figuring it out.

So is there anything timeless we can say about design? Well, that’s what we’re going to try and figure out with the ‘Good Design Is’ project. As Christians, Josh and I believe that the Bible has a truly good story to tell about human history – genuinely good news about where we came from, who we are and where history is going. That good news, that ‘gospel’ to use the Biblical term, affects everything. And that includes design.

This means the Bible has a better story to tell than any single culture, any design movement, and even (and this might be sacrilegious…!) than Dieter Rams – as much as Josh and I are massive fans. Fifty years on, we think there’s wisdom in re-examining ‘Good Design’ in the light of that truly good story. The gospel is timeless – and so if we use that as our starting point what might we find out about design? At the very least, it should spark some interesting conversations along the way!

Before we dig into that, however, we first need to look at why the idea of ‘Good Design’ warrants our attention at all.

Design is shaped by Culture

Understanding what makes a design ‘Good’ is important because design itself is important. Now, admittedly we’re pretty biased towards thinking that’s true (being designers and all) but hopefully by the end of the article you’ll see where we’re coming from. For instance, design is important because it’s inextricably linked to culture.

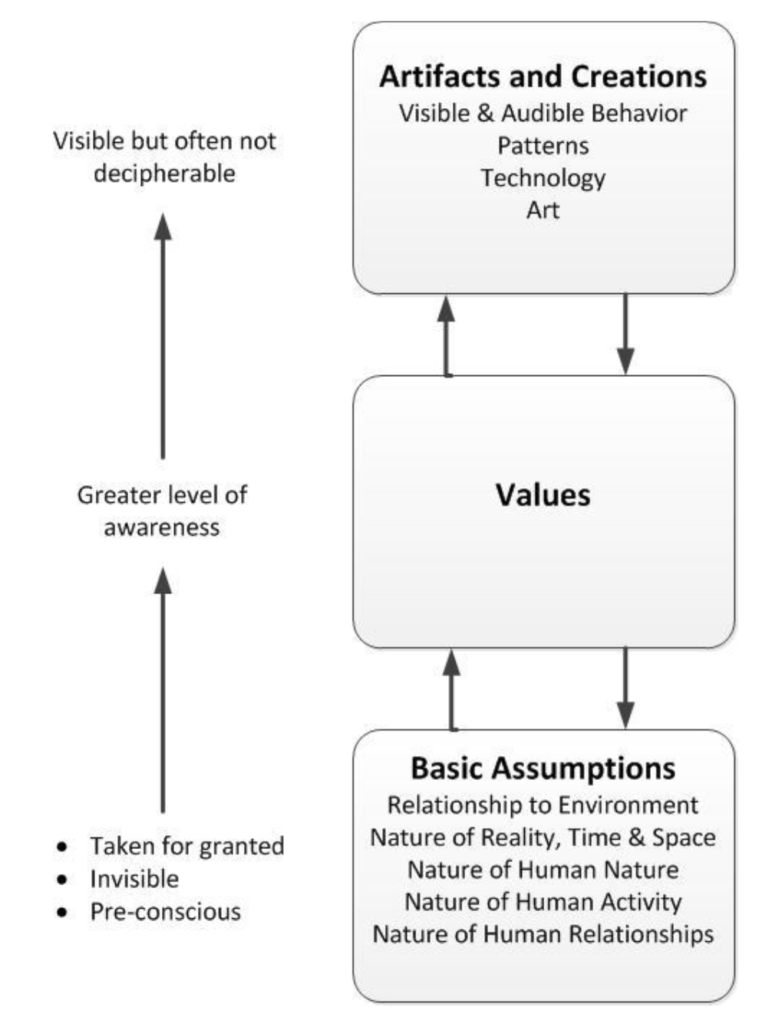

The idea of culture is a bit fuzzy and hard to pin down, but I’ve found the model below to be really helpful. At its deepest level, Culture is founded on our assumptions – things so basic we don’t even realise they’re not facts, like ‘education is important’ or ‘the washing machine should live in the kitchen’. You could call these ‘taken-for-granted’ assumptions, things that seem beyond debate if you’re a member of that culture. One rung up we have our values – conscious ideals which we count as important to us. And finally we have cultural artefacts – things like the way we behave, our clothing, our art or our technology and products. Collectively, these three elements form our cultural tapestry.

This means that what we design (and the way we design it) flows from our cultural assumptions and values. For instance, I have a beautiful pair of antique grape scissors at home, a product deeply entrenched in Victorian culture with their focus on manners and table etiquette. The assumptions of politeness as the highest end led to a dizzying array of behavioural artefacts – etiquette for every occasion, including how to eat and specifically how to eat grapes. Enter the need for grape scissors, a product flowing directly from the culture of the time. It’s maybe a bit of a flippant example, but there’s no other culture in which Grape Scissors would have emerged. The design was a direct result of the Victorian cultural context.

Or how about design movements as a whole? Arts and Crafts was born in a culture grappling with the social effects of rapid industrialisation, for example, and flowed directly from the values of people like William Morris. He valued social reform and staunchly opposed industrialisation, and his design philosophy flowed out of that. And whether its a conscious decision or not, this occurs for all of us as designers.

We live and breathe our cultures, and so whenever we put pen to paper we aren’t designing in a vacuum. Artists, designers, ‘creatives’ of all types – no matter how timeless you think your new work is going to be, the truth is that you are enmeshed in your culture and worldview. And that means our cultural assumptions, both good and bad, can be embodied in the things we design and make. For instance, did you know that some people once argued planned obsolescence was a moral imperative? To get the USA out of the Great Depression in the 30s, economists like Bernard London argued obsolescence was ethical because it would stimulate the economy and lift people out of poverty. The way products were designed in the 1930s grew out of the cultural assumptions of the day, and that has left us with a crisis of consumerism.

Similarly, it was only in 2011 that the US started using female crash test dummies. Introduced in the 1950s, crash test dummies were based on the 50th percentile male, reflecting the cultural assumption of the day that a man would be driving. It took 61 years for that assumption to be challenged, resulting in serious risk for female drivers. The way we test products, even, flows out of our culture.

If we are serious about designing good products, we need to realise that our starting point isn’t a blank sheet of paper – that we are influenced, consciously and unconsciously, by the cultural air we breathe. It’s critical, therefore, to grapple with what ‘Good Design®’ actually is, or we might forever tossed to and fro on the winds of our cultural context.

Culture is shaped by Design

But as well as design being influenced by culture, the reverse is also very much the case – design shapes culture. It’s as if the river of culture has torn boulders off some distant mountain and rolled them to where they now rest, huge rocks dotting the flow of water. But those rocks also shape and direct the river, steering it towards a new course. Art and design are culture-making exercises – the products we use, the films we watch, the graphic design we see all around us informs and shapes the culture we live in.

If you think back to the diagram above, cultural artefacts are at the surface level – they are what communicate the values and assumptions of a culture most clearly. And design is an excellent example of that – when William Morris created a hand crafted chair in an age of industrialisation it communicated his values and shaped the culture around him.

The excellent book ‘Why we make things and why it matters’ talks about the way craftspeople can embody meaning in their work. Just like words carry explicit meaning, so objects carry meaning implicitly, they gently explain to the user what the designer or maker valued, what they thought was important (or not), and what their view of the world is. Whilst it’s true that some products change the course of a culture by themselves (think the iPhone, the television, or even the humble fork), that’s not the case for most. But ALL products communicate culture, all products have a voice which speaks the values and assumptions of the designer. Although this voice might be small, when multiplied by millions of products across the world it becomes a gigantic rudder, helping to steer culture one imperceptible design decision at a time.

Take a look around the room you’re in, or consider the products you’ve designed yourself and think about what cultural values and assumptions they communicate. In what direction are they moving culture? Sometimes these things can be very straightforward (a shower communicates a culture that values personal hygiene), or sometimes they might be a little more veiled (do the walkman and iPod suggest music is valued more for self-expression than for building community?) – but whatever the case, every design has something to say.

As this project goes on we’ll take a look at all of the many questions this idea raises – that’s one of the reasons I think this will be an interesting journey – but hopefully for now we’ve shown that design and culture are inextricably linked. What we design, how we design it and who we design it for impacts our culture at large, even as the products themselves are consequences of the culture. It’s the stream and boulder analogy – design influences and is influenced by culture.

So that’s the first reason design is important – it is totally bound up with our culture, and each designed object communicates cultural assumptions and values, sometimes without the designer even realising they are doing it. Humans are culture builders, and design is one of their tools. And so we need to pay attention to it. What makes a design ‘Good’ is a really important question.

Design is for People

The second reason design is important is a little less esoteric (and will take much less time to explain…!). The second reason design is important is that it’s for people.

The whole spectrum of art, design and engineering builds culture, but there is something the ‘applied arts’ do which a sculpture or a movie don’t. People use designed objects. They embed them in their lives and daily routines in a way that they don’t with a beautiful painting or symphony.

Now, this is not to denigrate music or sculpture or dance – those forms of art communicate to the heart and minds of the audience in a way that the applied arts normally don’t. It’s a different way of interacting with people, not a better or worse one.

But because applied arts like Graphic Design or Architecture are used by people, the consequence of a design being good or bad doesn’t just affect them on an intellectual or emotional level – it affects their life too. A badly composed piece of music can disappoint – a badly designed car can kill. That’s an extreme example, obviously, but it gets the point across. Design is important because people use designed objects – and that gives designed objects a real power to influence people’s lives.

One thing that we’ll come back to more and more as the project goes on is that designing something for someone is an act of love – an opportunity to love our neighbour as ourself. Because the applied arts are used, designing something that actually works as intended to is really important! Phoning it in when designing a shoe or a chair can result in anything from mild frustration to chronic back pain – designed objects are used, and so designing well is an act of love for the user.

This is another reason why it’s important to grapple with the idea of Good Design. In the early modern period the prevailing view in architecture was a sort of functional utopianism, houses as ‘machines for living in’, as Le Corbusier put it. That was a cultural statement, but it resulted in real houses and neighbourhoods that (ironically) just didn’t work. People aren’t machines, and there is more to a city than efficiency – it turns out the large concrete blocks beloved by modernist architects didn’t cut it for actual human beings. But because these were designed objects for people, not just abstract theories confined to a library somewhere, these neighbourhoods had lasting impacts in the real world, affecting real people for decades to come. Check out the Bijlmer neighbourhood in the Netherlands for a stark example. Because design is for people, whether it is Good or Bad has real consequences. Design can either bless or curse, and so it’s important to engage with what makes a design truly good.

Good Design is Important

Design, then, is important because it creates and is influenced by culture, and it’s important because it’s used by people. Good Design is Important, and so a project like this is worth getting stuck into. If we believe that Christianity has a better story to tell than the culture around about, and if we believe that story impacts every single facet of our life, then we owe it to the people engaging with our products to explore how it impacts design.

Over the next weeks and months, we’ll be posting articles exploring different facets of good design – Good Design is Human, Good Design is Hard, Good Design is an Act of Love. If possible, we’ll also be interviewing some Christian designers and creatives to understand more of how their faith affects the way that they work. This definitely won’t be the final word on design (apart from anything Josh and I will be just as influenced by our culture as Dieter Rams was – although we will do our best to be aware of that as we write!), but for the reasons we’ve looked at, this is still a really important exercise. If it encourages us to begin thinking about design with the mind of Jesus then it’s definitely worth doing. And whilst this project might be of most use to Christians grappling with design, we’d love to invite folk of any faith and none to follow along and see what they think. Good Design is Important, and so we all need to wrestle with it.